At Heartland, we focus on stocks trading at low valuations as part of our 10 Principles of Value Investing™. But how we measure a company’s intrinsic value matters, as does the context surrounding those calculations. For example, while we will utilize broad-based valuation measures such as price to earnings, price to cash flow, and price to book value, we also apply specific metrics that we deem most appropriate to each company and its peers.

In the case of a bank stock, for instance, price to tangible book value is probably the most relevant multiple, as these financial institutions are asset-driven businesses generating value by taking deposits, making loans, and through their financial holdings — all of which are fully reflected in their balance sheets. Yet it wouldn’t make sense to use tangible book to assess a software company whose value resides not in physical assets but in intellectual property, research & development, and future cash flows. For these types of businesses, enterprise value to sales may be a better metric.

After determining the right gauge, another important consideration is how each company’s valuation could change over time. For every company in our portfolio or on our radar, we establish a range of price targets that reflect how the market is likely to assess the company’s worth under different circumstances, including under a worst-case scenario. This price, which we refer to as our max downside loss target, reflects how we think a stock’s value could be affected by a severe shock like the global financial crisis (GFC) in 2008 or the economic shutdowns during the global pandemic in 2020.

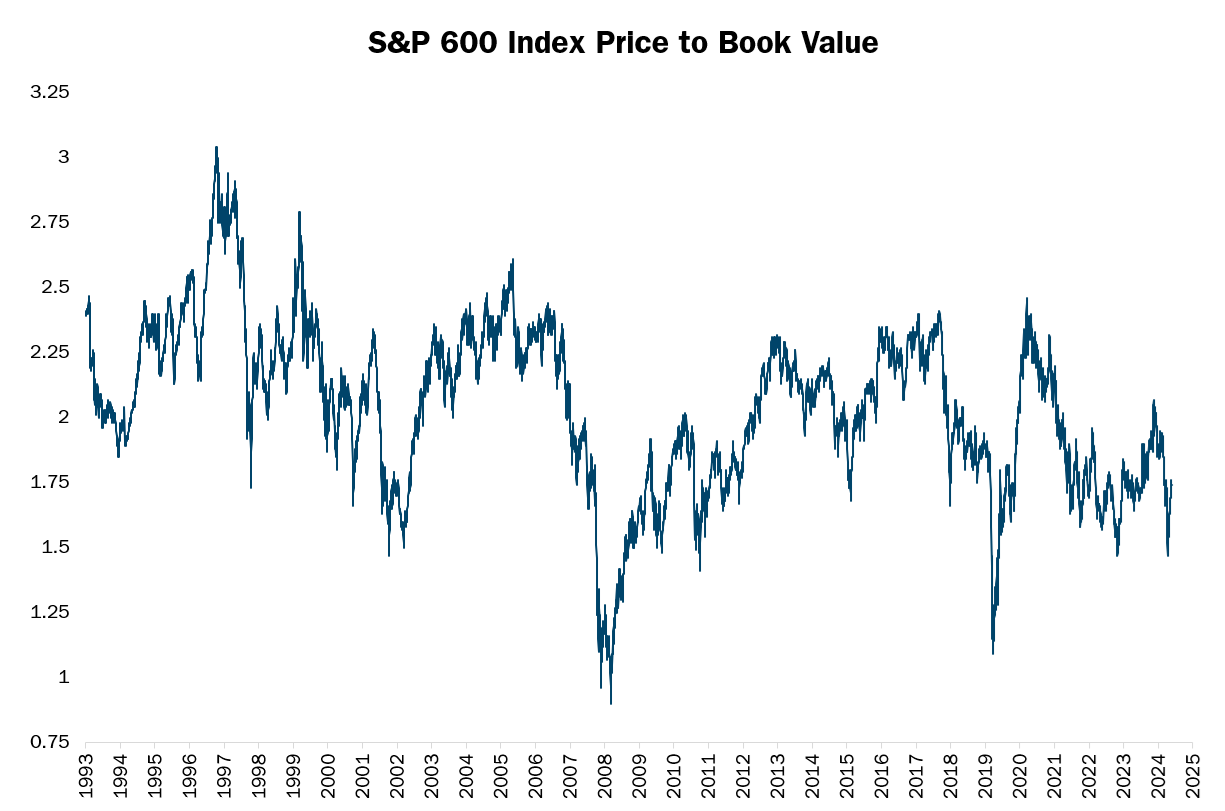

Sometimes, the value the market ascribes to a company under normal ‘base-case’ circumstances could be markedly different compared to a worst-case scenario. For example, the S&P 600 Index of small stocks has traded at an average price-to-book value of 2.05 over the past three decades. Yet during recessions that grew out of the GFC and COVID-19, the S&P 600’s multiple fell to around 1 times book value, as revenue, profit, and cash flow pressures led to multiple compression (see the chart below). If this were a stock, such experiences could help us establish a max downside loss target for the shares.

Source: FactSet Research Systems Inc. Daily data 1/3/1994 to 5/20/2025. The data in this chart represents the Price to Book Value of the S&P 600 Index. The S&P SmallCap 600® seeks to measure the small-cap segment of the U.S. equity market. The index is designed to track companies that meet specific inclusion criteria to ensure that they are liquid and financially viable. All indices are unmanaged. It is not possible to invest in an index. Past performance does not guarantee future results.

Setting a max downside loss price on a stock serves several purposes. For starters, those targets help us establish realistic expectations for every stock we own or consider. Always having a sense of the worst-case scenario also helps with timely decision-making, as we won’t have to assess a stock’s value on the fly during a rapidly unfolding crisis. This allows us to act and react quickly, whether that involves selling, holding, or adding to our position. Moreover, in the case of a stock that we don’t already own, having a sense of the security’s max downside price can help us decide whether to initiate a position once the worst of the crisis is likely over.

By taking this approach, we ensure that valuations aren’t just a risk-management tool, they also allow us to take advantage of situations if and when opportunities arise. In our opinion, this is the best away to approach challenging environments — by thinking defensively and opportunistically at the same time.

©2026 Heartland Advisors | 790 N. Water Street, Suite 1200, Milwaukee, WI 53202 | Business Office: 414-347-7777 | Financial Professionals: 888-505-5180 | Individual Investors: 800-432-7856

Past performance does not guarantee future results.

Investing involves risk, including the potential loss of principal.

Value investments are subject to the risk that their intrinsic value may not be recognized by the broad market.

There is no guarantee that a particular investment strategy will be successful.

Small-cap investment strategies, which emphasize the significant growth potential of small companies, have their own unique risks and potential for rewards and may not be suitable for all investors. Small-cap securities are generally more volatile and less liquid than those of larger companies.

The statements and opinions expressed in the articles or appearances are those of the presenter. Any discussion of investments and investment strategies represents the presenters' views as of the date created and are subject to change without notice. The opinions expressed are for general information only and are not intended to provide specific advice or recommendations for any individual. Any forecasts may not prove to be true.

Economic predictions are based on estimates and are subject to change.

Heartland’s investing glossary provides definitions for several terms used on this page.